Medieval Muslims loved their cats so much

Cat shelters, cat shoes, cat jewellery, and more from the Islamic Middle Ages

Cats didn’t always have it so easy in the medieval West. Maybe it was wasn’t as bad as you think—cats were popular pets in Europe in the Middle Ages and people indiscriminately killing them didn’t cause the plague—but there’s no doubt that they were seen as less useful than dogs and, in some cities at certain times, subject to violence. Their cousins in the east, however, were luckier. In fact, it sounds like was pretty great to be a medieval Muslim cat.

The Prophet Muhammad was reportedly a cat lover and strongly condemned the hurting or killing of any cats whatsoever. A number of hadith tell stories about him and his feline companions. One cat in particular, named Muezza (Arabic: معزة), was supposedly the prophet’s favourite. It’s said that Muhammad was dressing one day to go to morning prayers, but discovered Muezza fast asleep on the sleeve of his robe. Rather than disturb the cat, he took a pair of shears and cut the sleeve off so Muezza could nap undisturbed.

(Reading about Muezza led me to find out that there is also a brand of halal cat food in the UK named after Muezza!)

This is actually strongly disapproved of in Islam.

One of Muhammad’s companions was known as Abu Hurayra, a nickname that literally means “father of a kitten”, because of his attachment to cats. Another story tells us that one of Abu Hurayra’s cats saved the prophet from a venomous snake one day. As a gesture of thanks, Muhammad stroked the cat, leaving behind the marks on its forehead which some cats have today. (Some versions include that he also endowed all of cat-kind with the ability to land on their feet.)

I can only assume it’s a coincidence that the forehead marks look like an “M” for Muhammad…..unless?

But it wasn’t just the prophet himself who loved cats! They occupied a unique place in the medieval Islamic world. The Middle East and Mediterranean are famously full of stray kitties nowadays, and it seems that 500 years ago, things weren’t too different. Medieval Europeans who travelled eastward were baffled by both the sheer quantity of free-roaming cats and the affection lavished upon them by locals. Flemish nobleman Joos van Ghistele wrote of his surprise at seeing a cat shelter in Damascus in the late 15th century CE, and a 13th century CE Mamluk sultan apparently mandated that all the strays of Cairo be taken care of by the local government. An English visitor to Cairo in the late 19th century attested that the sultan’s wishes were still being upheld, much to the exasperation (and expense) of the chief judge, to whom the responsibility fell.

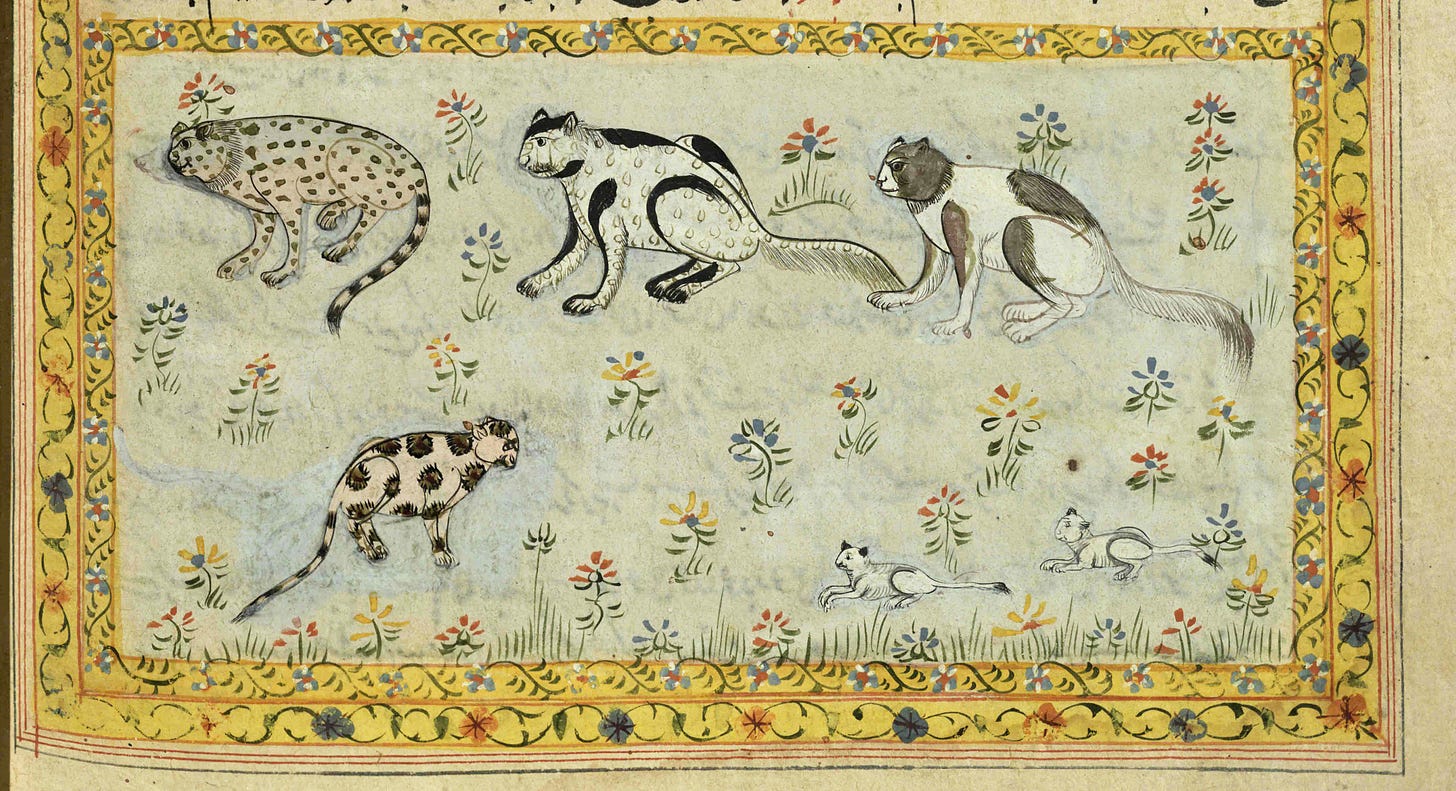

Cats from a Persian manuscript, 17th or 18th century

As well as collective care for strays by the community, a number of sources describe cats’ status as beloved pets for people from all levels of society in the medieval Islamic world. For much of the Middle Ages in Western Europe, pet ownership was seen as an indulgence afforded primarily to noblewomen and monks. High-ranking men might have owned hunting dogs, but these animals served a largely utilitarian purpose. The keeping of animals for emotional companionship would have been rather taboo for a Christian man of the day. Muslim men, whether nobles or humble labourers, don’t seem to have been subjected to the same stigma surrounding their pets.

Prince Rokn-al-Dawla of the Deylamites (in modern day Iran) reportedly had a pet cat that he was so fond of, petitioners would attach written requests to its neck to make sure that prince received them. One Sufi sheikh is said to have had shoes made for his cat so that it could sit with him on his prayer rug without snagging the fibres on its claws. Women doted on their cats, too, with one Persian source reporting that it was common for noble ladies to adorn them with jewellery and even dye their fur. Here’s one 11th century CE poet from Gorgan (modern day Iran) on his cat:

I have a cat whose foot-pads I dye with henna

before I put henna on my own newborns.

Then I tie cowrie shells to her collar

to repel the harm of evil eyes.

Each day, before I feed my family, I see that she gets

our choicest meats and purest waters.

Cat figure, Persia, 12th-13th century CE

The famous Persian poet and mystic Hafiz was embroiled in a bitter rivalry with a fellow writer, Imad Faqih Kermani, and constantly battled with him for the favour of the Shah. Imad had apparently taught his cat to bow alongside him in prayer, which the Shah regarded as a miracle, though Hafiz was rather less convinced. He wrote a rather petty poem subtly denouncing Imad as a charlatan and comparing his admirers to songbirds who would foolishly walk right into the cat’s claws:

O gracefully-walking partridge, whither goest thou?

Stop! Be not deceived because the zealot's cat says its prayers !

(Note: if you haven’t read any of Hafiz’s poetry, you’re missing out! He was a brilliant writer and satirist. Some of my favourite verses of his include this one where he compares life to a game of chess that you lose to God and this one where he recommends getting drunk with your plants and pets.)

I have shared a joke before on Twitter by Nasreddin, a legendary medieval Turkish humourist. Let me close this post by sharing another Nasreddin joke, this time about his wife and his cat:

After the Hodja got a liver recipe from his friend, he bought some liver. Nasreddin loved liver and he wanted to eat it very often. But everytime he brought livers, he couldn't eat it because his wife said that the cat took the liver and fled away.

One day the Hodja became very angry and said: “Woman, I brought liver! Where is it?” “Oh”, said his wife. “The silly cat took it and fled away.” At this same time the cat was in the room.

The Hodja caught it, brought a steelyard and weighted the cat. Then he said: “That is exactly two kilos. And the liver which I brought was also two kilos. Now tell me: If that is the liver where is my cat, if that is the cat, then I want my liver.”

The husband of a greedy woman weighs the cat that supposedly ate all the meat that he bought for his guests. From a Persian and Arabic manuscript made in India, 1663 CE.

Note: the reasons why the Islamic and Christian worlds of the Middle Ages displayed an apparent cat/dog divide are complex and can’t be boiled down just to religion. The purpose of this post is not to ascribe certain intrinsic characteristics to any one faith or culture—just to share some fun historical facts about cats!

Note #2: Edited to correct information about the poet Abu Amir, who lived in the 11th century, not the 10th, and was from Gorgan rather than Egypt

Abu ‘Amir (the author of your cat poem) lived in the late 11th century CE, and not in Egypt but Gorgan (northern Iran), as indicated by his surname al-Jurjani. Otherwise, nice work.

Another fabulous post!! You are opening up whole new areas of human (and feline) history and culture to this ancient reader. And your writing voice is such a delight!