Why did medieval people invent so many collective nouns?

A pride of lions, a paddling of ducks, and....a herd of harlots?

The proper term here would be a “riches” of martyrs, apparently

Here’s a great paper for you to have a look through: a 25-page list of medieval collective nouns, aka words for groups of things, compiled by Maurice L. Hooks. Along with the more conventional terms for things like lions (a “pride”) and fish (a “school”), you’ll find words to describe gatherings of practically every creature under the sun, from a paddling of ducks to a herd of harlots and an eloquence of lawyers. Here are a few more highlights:

a dissimulation of birds

a destruction of wildcats

a court of coots

a melody of harpists

a sentence of judges

a superfluity of nuns

an unkindness of ravens

a skulk of thieves

a true-love of turtledoves

an impatience of wives

I mean, they certainly look impatient

I can’t recommend enough that you read the full list, which its compiler describes as “practically useless and academically curious”: there are a few hundred collective nouns in there and nowhere near the space here to share all the good ones.

With so many terms listed, and so many oddly specific and seemingly ironic ones at that, it is hardly unreasonable to wonder how all of these curious words came about, and indeed whether medieval English people would actually refer to a “discretion” of priests or a “worthlessness” of jugglers in casual conversation. To answer these questions, we can start by looking at the sources where these collective nouns were found.

Maurice L. Hooks’ paper cites numerous medieval manuscripts, but the majority of his collective nouns can be found in one particular work, The Book of Saint Albans, which was printed in 1486 but compiles knowledge and essays from several earlier sources. A sort of one-stop-shop guide for medieval gentlemen, the Book contains information about hunting, hawking, and heraldry, matters that were considered essential knowledge for any aristocratic man of the day. Hunting, in particular, was a hugely important mode of social engagement for the medieval upper class, and almost every person of noble status would have participated.

The hunt, France, 15th century

While the common folk hunted largely for sustenance, using the easiest means available, the aristocratic hunt was surrounded by highly developed sets of rules and customs that had steadily grown in complexity and importance over the preceding centuries. As well as The Book of Saint Albans, a number of other medieval manuscripts lay out these practices in eye-watering detail, including the early 15th century Master of the Game by Edward, second Duke of York1. The Master of Game includes specifications for who was to be involved in a hunt, what sorts of tactics were acceptable, how different types of animals should be pursued, what types of dogs and birds of prey should be used in various scenarios, what qualities to look for in human and animal members of a hunting party, and many other nuances that defined the “proper” hunt.

These rules were innately hierarchical: there was a clear distinction in how the lord of the house and his guests should participate compared to their servants and gamekeepers, as well as guidelines for the less strenuous types of hunting noble ladies should be allowed to take part in. Hunting by pursuit and killing at close quarters was placed above hunting with traps or bows, which were considered cowardly and improper methods for a man to use.

These rules extended beyond the human and into the animal world, delineating “good” prey (such as the stag and boar) from “bad” prey (such as the wolf and wildcat). Good prey animals were ascribed positive characteristics—especially the stag, which was admired for its wisdom, strength, and noble spirit, meaning that its hunt required a higher degree of respect for the beast and conferred a great deal of prestige on its hunters. Animals ascribed negative characteristics—especially the wolf, which was supposedly filthy, violent, and sneaky—were afforded far less respect during the hunt, meaning that they could be killed in any way by anyone, even commoners.2

Women were allowed to hunt with falcons, which is cool

There has been extensive study of how this hierarchical, rule-centric hunting culture served as a way to emphasise the social structure of medieval Europe, drawing clear boundaries between roles of those at different levels of society and exerting a humanising, moralising force on wilderness that brought the beastly under man’s control. By knowing and applying all of the rules required to participate in this ritualised form of hunting, the nobility could affirm their status to their peers and so-called inferiors, and assure that those who did not belong to their world were unable to take part in its practices.

Killing a wolf, France, 15th century

One arm of this exclusion apparatus was hunting terminology, the importance of which was emphasised by almost every medieval author who wrote on the subject. Applying hunting rules in practice was not enough: it came to be accepted by the Late Middle Ages that a good huntsman should be able to converse knowledgeably about every hunting subject, using the proper language to demonstrate his understanding. Here’s a passage from the 15th century that sums up the intention of this language well:

And as the book says Sir Tristam devised good fanfares to blow for beasts of venery, and beasts of the chase and all kinds of vermin, and all the terms we still have in hawking and hunting. Therefore all gentlemen who bear old coats of arms ought to honour Sir Tristram for the goodly terms that gentlemen have and use, and shall until Doomsday, that through them all men of respect may distinguish a gentleman from a yeoman and a yeoman from a villein.

-Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte d’Arthur

Note the final sentence: these terms indicated one’s standing in the world, letting people know whether they were speaking to a gentleman, yeoman, or villein, ie someone of the upper, middle, or lower class, respectively. This specialist language and the overarching hunting culture were seen as necessary to indicate inherent differences between the social classes. Though they were perhaps only acknowledged to be passive markers of status, they of course actively reinforced class structures, preserving the social order that was seen as fundamental to societal wellbeing.

Sorry, did you just call spraintes “otter poop”? I don’t think this is going to work out.

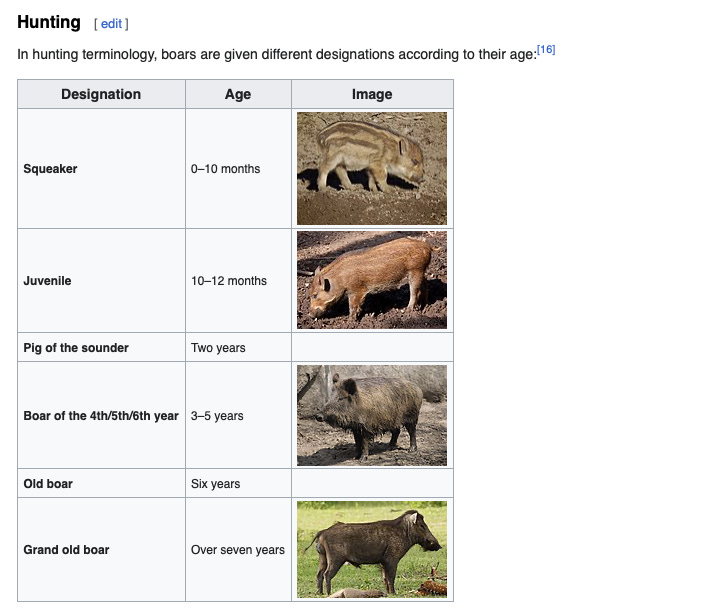

Thus, for every situation there was not only a rule but a word: different words for every different animal’s home, behaviours, stages of life, and even droppings. And, of course, collective nouns, known as “terms of association”, to distinguish whether one was stalking a single quail or a bevy of quails, a lone wild pig or a whole sounder of the things, and so on. This emphasis on terminology continued for some time into the early modern period: in one 16th century hunting book, the author complains that the youth of today think that all animal dung is called the same thing, when in fact there are five possible terms for droppings depending on which creature created them.

Kids these days could never tell a squeaker from a pig of the sounder

Lists of these words were included in the popular hunting texts of the day, and added to gradually as the works were transcribed, translated, and shared around Europe. As creating increasingly specific and obscure terms became popular among nobles, the practice began to take on a humorous element, with some authors including words that may not have had much practical use, but played jokingly into hunting conventions and the culture of the day. It’s hard to know which ones were serious, which were not, and which were perhaps somewhere in between, but it’s safe to assume that not every word found in Hooks’ compilation was used in everyday speech. Although they can be found in The Book of Saint Albans and other hunting books, and many can be found in literary works, suggesting that they may have at least been used as poetic devices, there was no doubt an element of pure humour that arose from intentionally placing outlandish, novel words alongside more familiar ones.

Many of these words survive in everyday English speech today, and their popularity is often attributed to The Book of Saint Albans, which was wildly popular as one of the first widely available hunting treatises. Thankfully, nowadays if you refer to a pride of lions, a gaggle of geese, or a flock of sheep, your conversation partner isn’t likely to start making inferences about your land holdings or annual income. Nevertheless, it’s a testament to the importance of hunting in the medieval world (and the lack of other viable hobbies for 15th century men) that so many remnants of their obsession have carried over into the modern day.

Edward, second Duke of York was also responsible for this charming list of over a thousand dog names, which I have tweeted about before

Because of this special status afforded to wolves in Great Britain, human outlaws in medieval England could be designated caput lupinum: literally “wolf’s head”. This meant that they, like the wolf, could be killed by anyone at any time without penalty.

I downloaded the PDF and it is so great. A “city” of badgers!

It did not include my favorite, though, an “ostentation” of peacocks.

Super interesting read! English really is such a cool language :)