Why medieval artists drew ancient Romans in medieval clothes

Or, how the French stole Julius Caesar in 1200 AD

This is a 15th century manuscript drawing of the coronation of Alexander the Great. Alexander, who lived around 350 years before the birth of Christ, is shown in medieval clothes, being crowned by…Christian clergymen? Why did the artist think that ancient Macedonia looked like this?

I’ll give you a hint: the probably didn’t! but let’s take a closer look at why.

This is a common occurrence in medieval art, particularly illuminated manuscripts. Almost every character from classical antiquity receives similar treatment. Here’s Julius Caesar and Pompey:

Hmmm, very medieval. But why?

The conventional assumption is that artists simply didn’t know what the ancient world looked like. If they had known, they would have drawn it accurately, right? By extension, it seems to follow that we ended up with more realistic artwork after the Middle Ages because of a revived interest in the classical world, history, and scholarship. Knowledge that was lost was somehow found again.

That seems to be the consensus among Twitter users, anyways.

There’s a widespread belief that medieval life was characterised by ignorance of classical thinking and culture. Sandwiched between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance (literally: “rebirth”), it’s a time in human history that seems to be thought of as a thousand-year intermission in serious scholarship. Rome fell, the library of Alexandria burned, all of that knowledge was lost to time—but only temporarily, of course, because we found it all again around the year 1500 and everyone became enlightened and could finally draw togas properly.

As with many things in history, of course, it’s not quite that simple.

In the East, Roman traditions and governance carried on for another thousand years until 1453, when Constantinople fell. What we know as the “Byzantine Empire” was known to its citizens simply as the “Roman Empire” and they celebrated ancient thinking as part of their own culture. Byzantine scholars copied down thousands of ancient texts from fragile papyrus onto more durable parchment, preserving them for future generations, although they didn’t think of it as preservation. With such a vast corpus of Greek and Roman writings available to them, they didn’t perceive any scarcity or threat to their libraries of scrolls. They were simply choosing the works that interested them and creating copies for scholarly study.Even in the more fragmented west, writers and scholars across Europe were constantly copying and studying classical texts. As discoveries of previously-unseen papyri are rare, almost every ancient text we have today is the result of medieval scribes’ efforts.

They made Isidore of Seville the patron saint of the internet because he preserved so much information and also made a lot of spurious claims

Of course, not every work was copied. Poetry and theatre interested medieval writers far less than rhetoric, philosophy, and science, so the latter fields are comparatively overrepresented in the extant corpus. All post-medieval classical study is working largely with what appealed to copyists of the Middle Ages. They are the interface through which we access the ancient world.

While these texts remained in Latin originally, they were gradually translated into more accessible languages with the hopes of disseminating the wisdom therein among the laypeople. So successful were they at this task that in the 12th century, Marie de France wrote that she was sick of the classics:

“I had begun to think that I might make a good story of them, and translate from the Latin into French. But such a project would scarcely have benefited me since it had already been done so much by others.”

Here’s Marie, can we make her patron saint of hipster bullshit?

Perhaps a bit melodramatic to say that all of Latin literature has been “done”, but what’s a writer if not dramatic? Anyways, her words are a reflection of the abundance of classical texts in medieval scholarship. If you studied philosophy, rhetoric, medicine, law, or basically anything else for most of the Middle Ages (although that was most of the things you could study because degrees in business management hadn’t been invented yet), you would be reading a lot of Greek and Roman texts in Latin. However, the words you would read would have probably passed through a few sets of hands first, copied from a copy of a copy of a copy and so on.

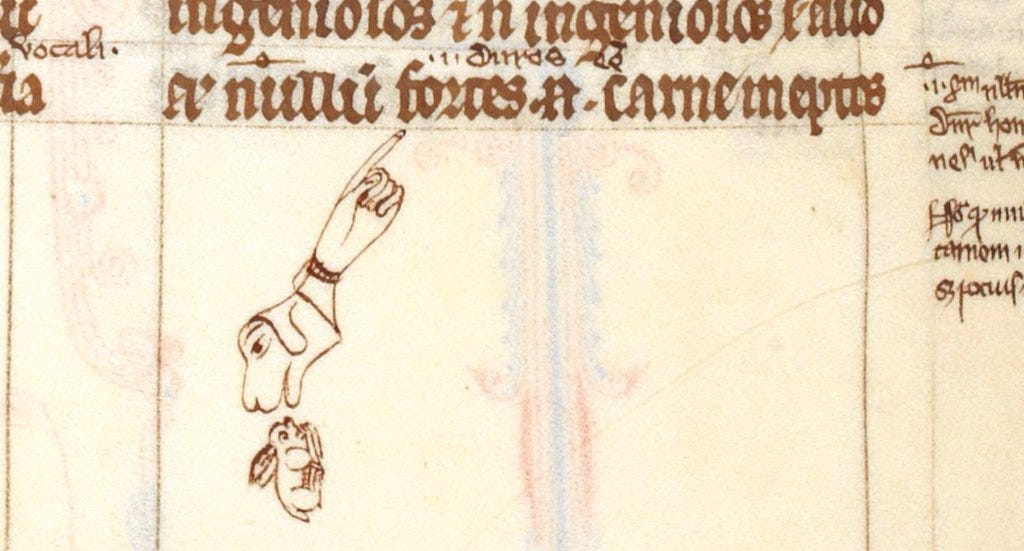

Once you had your own copy of a book, it was standard practice to add notes or highlight important bits however you liked, as someone has done here

Marie talks about making a “story” of Latin texts. She is alluding to the medieval tradition for the copyist to take a critical approach, commenting and altering as they wrote with the intention of improving the original. Thus, each version of a text was unique to the scribe who created it. While the idea of taking a red pen to Cicero would horrify a modern scholar, historian Jaques Monfrin summed up the medieval attitude rather succinctly: "as long as it is transcribed and translated, there is no reason not to update it or improve it by supplementing it with information drawn from other sources." To copyists of ancient texts, who felt that their pagan sources needed to be suitably adapted for a Christian audience, “improvements” often included heavily rewriting to align with contemporary values. These weren’t seen as falsehoods but necessary amendments to modernise the text.

Instead of pointing at anachronisms as a means of proving that medieval writers were ignorant of the ancient world, it could possibly be more correctly said that medieval writers were all too aware of the ancient world and its differences with their society, and it is because of that awareness that we see so many anachronisms in medieval literature and art depicting antiquity. They knew that they were adapting historical, pagan texts that conflicted with their society’s morals, and took on the role of content editors preparing an unfinished draft for publication. Even historical accounts were not safe from the medievalisation treatment.

This culture of rewriting was very convenient to medieval society, which invoked historical precedent as a means of legitimising power: a common conceit was for written stories to include a fictitious prologue about how the text was actually discovered in an ancient library/abandoned castle/magical forest and the supposed author was really just sharing the words of some unknown authority from days gone by. The author didn’t think it was true, the audience probably didn’t think it was true, but it still got the message across: “These are ancient words, respect them. No, I didn’t just make them up, thank you very much.”

Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords books is no basis for a system of government!

The author of one medieval French poem about the ancient world claims not to have written it but found it in an ancient book, and that the truth of the content could be verified by its age. The content in question, of course, is his own. For instance, in his preface, he writes:

“This is what our book taught us: Greece has the first renown of chivalry and of learning. Then chivalry came to Rome, and with it the sum of learning, which now has arrived in France.”

Pretty simple, no? In one fell swoop, he’s rewritten a thousand years of history, justified chivalric culture, and established France as the true inheritor of ancient empires, therefore making his kingdom the most legitimate one. Very convenient, Monsieur.

In the same vein, attributing actions to heroic figures such as Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great was a way of endorsing those actions. Unconcerned with objective truth, biographies became more like fictional stories. By rewriting not just the events but the historical setting of the stories, making its inhabitants medieval archetypes who lived Christian lives, authors could emphasize the meaning these ancient figures had for the Christian society of the present day.

Polytheism? Not in my good Christian illuminated manuscript!

So, in medieval “histories”, Caesar was given a Christian wedding and burial and Alexander was crowned in the Christian tradition, with intention of making them more effective vessels for the author’s ideas. So popular were these adaptations that they became the de facto versions of their protagonists’ lives and spawned all number of derivative works in the latter half of the Middle Ages. Historical figures became archetypes who belonged to a distinctly medieval literary tradition: entirely different characters to their real-life counterparts.

The image of Caesar above is taken from a copy of Le Faits des Romains, a French account of Caesar’s life written in the early 13th century and copied at least 50 times before the end of the Middle Ages. At the time of its creation, the aristocracy of France were a experiencing a systematic stripping of their lands, wealth, and privileges as the king consolidated the throne’s power. This may give some insight into why a story of Caesar’s abuse of power and downfall at the hands of his own “court”, so to speak, resonated with the nobles of the day. Though based on Roman accounts of Caesar’s life, the author made the edits they saw necessary to create a setting and characters relatable to readers. The central figure’s tyranny is emphasized and his opponents are made more sympathetic, especially the Gauls, who inhabited what is now France. The final message is clear: we should totally just stab Caesar. Also, vive la France.

Remember how Gretchen was talking about Caesar but she was actually talking about Regina George? That’s basically what they were doing

When illustrating Caesar and the other characters, then, it seems a bit more logical to dress them up in the garments of the day. Rather than create a conflict between medieval morals and pagan (=amoral) setting, the images were given the same makeover as the words. Classical Caesar is a Roman statesman who wears a toga, but medieval Caesar is a different guy, a chivalrous knight (before going mad with power) who would never ever make a human sacrifice in the name of Mars, so he needs to dress the part. Classical Caesar thinks the Gauls are barbarians who need to be subjugated, but medieval French Caesar thinks the Gauls are a very civilised bunch and worthy adversaries. And it’s actually the Normans who are the barbarians. Obviously.

Death of Cleopatra, Netherlands, 15th century

Using the past to legitimise the present isn’t uniquely medieval, of course, nor is bias and agenda in historical accounts. Since the Renaissance, almost every European state and empire has venerated the ancients, creating art and architecture in their image, claiming to revive the ideals of antiquity. What could be thought of as unique to the Middle Ages is the conscious, widespread alteration of the past to conform with the present, rather than vice versa. They didn’t emulate the Romans, they made the Romans emulate them. This staunch refusal to ape a bygone culture seems to be what has earned its writers and artists the label of “ignorant”. But if they were using the ancient world as a way of finding their way forwards, and we use it as a way of trying to go back, who’s more ignorant?

I'd suggest that another factor was the common medieval understanding of the relation between concepts, things, and images.

Broadly and briefly, since the ultimate reality of things was their presence as ideas in the mind of God, from which they proceeded into material actuality, the our understanding (i.e. intellectual "vision") of an idea was a glimpse of the true reality of a thing, more fundamentally "real" than the thing itself. The point of a painting or illumination was to engender this intellectual vision in the beholder. So, it didn't matter if you pictured Caesar wearing a toga or a 15th century French royal outfit, as these were merely material details which veiled the deeper reality conceptual reality of Caesar. What mattered was that seeing the image raised the mind towards the contemplation of the idea.

I don't know if I'm explaining this well, but once this principle is grasped it unlocks a fascinating dimension of medieval art (and writing for that matter) that makes the reasons for a ton of its stylistic tendencies click into place

This is such delightful, revelatory writing - I look forward to your future posts!