An 800 year old prayer book that's decorated with puns

Plus a little history of manuscript illustration

The images that adorn the margins of medieval manuscripts are often confusing to a layperson. Longstanding scholarly efforts to understand the meaning behind snail fights, murderous rabbits, beastly hybrids, and other curious medieval motifs have yielded an abundance of theories. Many are very convincing. News outlets such as Vox and The Washington Post have even featured a few! But a conclusive explanation will likely never be available, and the arresting visual weirdness of medieval artwork continues to be much more interesting and accessible to the mainstream than the nuances of medieval culture that influenced it.

Yet, the question of why medieval art is so strange continues to intrigue us, though it may not be the right question to ask. After all, when we talk about “medieval art”, we are really referring to a millennium of ever-changing and highly contextual trends across a rapidly developing continent. Though the prospect of a single simple answer that does not require us to understand all of that context is appealing, it is also unlikely. Perhaps a more realistic approach, then, is to narrow our focus and look at individual cultures, manuscripts, and even images.

Dr Betsy Chunko-Dominguez, an art historian who specialises in medieval marginalia, has given us an opportunity to do just that. Her paper “Playing on Timbrels” focuses on the Rutland Psalter, a 13th century English prayer book held in the British Library—and one of the most densely adorned manuscripts of its time. You may not have heard of this book by name, but its images have been circulated far and wide on the internet as it’s a classic example of that characteristic medieval oddness that many of us find so captivating. Though the Rutland Psalter contains many illustrations of a purely religious nature—mostly full page works and decorated initials—its hundred or so marginal drawings are the real attention-grabbers. Seemingly absent of scriptural themes, they depict a panoply of humans, beasts, hybrids, and monsters that fight, play, and dance across the pages, even interacting with the written text and floral borders.

Many of the figures are fully or partially nude and engage in crass gestures and poses. To a modern viewer, these silly scenes may seem wholly unrelated to the prayers that share their pages (not to mention vulgar and unfitting for a religious book). However, drawing on the earlier work of medievalist Michael Camille, Chunko-Dominguez shows that many of these drawings are very direct puns on the prayers of the psalter.

The Rutland Psalter, fol. 67r

In his seminal work Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, Camille pushes back on the notion that the marginal art of the Rutland Psalter is, as many scholars have assumed, “pure fantasy”— that is, with no defined intentions or meaning. Crucially, he highlights the fact that almost all manuscripts of this type would have been illustrated by a separate artist (or several) after the scribes had finished their work on the text. Therefore, Camille posits, it’s hardly unexpected that some of the artist’s work should be influenced by the writing. He cites as an example the illustration on fol. 14r, in which a decidedly pained-looking man clutches onto the page border while a serpent bites his foot.

At first glance, it’s easy to write this off as random and meaningless. But Camille points out the text directly above this interaction, from Psalm 9:

Exultabo in salutari tuo infixae sunt gentes in interitu quem fecerunt in laqueo isto quem absconderunt conprehensus est pes eorum.

I will rejoice in thy salvation: the Gentiles have stuck fast in the destruction which they have prepared. Their foot hath been taken in the very snare which they hid.

Unlikely to have drawn such a scene by coincidence, the artist has created a sly parody of the adjacent text and its reference to snared feet! Chunko-Dominguez provides many more examples. At the bottom of fol. 11r, we see two men locked in a wrestling match. One appears to have grabbed the other by the ear, and his opponent desperately tries to break his grip.

The same page contains part of Psalm 5, which begins on the opposite page with the words:

Verba mea auribus percipe Domine intellege clamorem meum.

Give ear, O Lord, to my words, understand my cry.

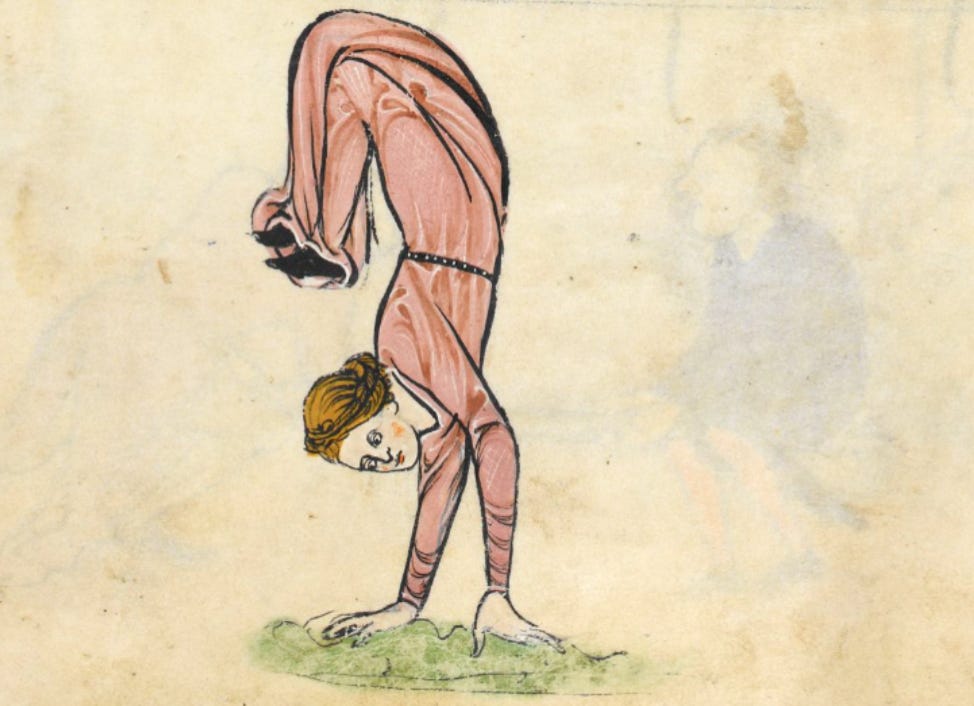

A clever inversion of the phrase “give ear”, now the ear is being taken by force: Hey, you! Give me that ear! On fol. 65r, we see a figure performing a handstand.

Inposuisti homines super capita.

Thou hast set men over our heads.

Which more or less speaks for itself. A particularly humorous example, fol. 87v contains the following vulgar scene, in which a monstrous sort of archer fires an arrow directly into the rear end of another humanoid creature:

The arrow has been attached by the artist directly to the word “conspectu”, meaning to see or penetrate visually: now the word is penetrating physically as well, an unwilling participant

Of course, there is still some ambiguity as to the purpose these puns served in relation to the text. Michael Camille seemed to favour a rather antagonistic interpretation, suggesting that the crudeness and irreverence of these illustrations were the artist’s way of hitting back at the scribe and even at the scripture itself and undermining the written word. Chunko-Dominguez theorises a more harmonious relationship, noting how the rich and dynamic imagery could have highlighted key textual themes in a manner that was engaging and memorable to the reader, forming a sort of dialogue between word and margin—not an argument.

Why are manuscript margins illustrated, anyways?

So entertaining are medieval margins to the layperson that it becomes easy to forget their raison d'être—the text itself. Of course, without a medievalist’s understanding of Latin scripture, remembering won’t do much good. In a sense, this is by design. Latin was not spoken among the uneducated in the Middle Ages, despite the fact that it was the language of all religious texts and services. This was hardly seen as problematic because average people were not meant to understand or engage directly with scripture, but rather rely on educated members of the Church to interpret it for them.

In large part, this stems from early Christian theologians such as Saint Augustine. In order to reconcile seemingly immoral aspects of the Old Testament (such as polygamy) with the New Testament and Christian teaching, Augustine established an interpretive framework that treated scripture as highly symbolic. Rather than believe that early biblical figures literally had six wives, as was written in the text, such a passage was meant to convey a much more cryptic and obscure meaning that was compatible with the supposed holiness of its subject.

Those things […] which appear to the inexperienced to be sinful, and which are ascribed to God, or to men whose holiness is put before us as an example, are wholly figurative, and the hidden kernel of meaning they contain is to be picked out.

-Saint Augustine, De doctrina Christiana

The underlying message is that those who read the Bible without proper understanding of how to identify and interpret its symbols risked drawing incorrect and harmful conclusions. Augustine tied this into a broader notion that scripture was necessarily symbolic in order to be impenetrable to the non-devoted reader, ie the “commoner”. Only the pious, erudite, and spiritually worthy could “pick out” the true intentions of the text, which they were obligated to do, in order to tell it to the little people and make them into better Christians. This idea was an influential one, and subsequent theologians throughout the Middle Ages deepened and broadened biblical analysis into a highly active and international field of study.

Augustine explains to the masses why it’s okay that he has six wives

In the centuries before the creation of the Rutland Psalter, most manuscripts were made by and for religious scholars like these and had wide margins: not for decoration but to provide space for the owner to add commentary, notes, disagreements, and other expansions upon the original text. Far from devaluing a book as they might today, these additions were often highly useful to subsequent owners of a manuscript, who would extend the discussion by refuting or building upon them with their own notes.

This definitely improves the overall reading experience.

Drawings, too, became part of this culture of commentary, where they could be added to the margins to bring attention or give weight to an annotation. One 12th century scribe at Canterbury Cathedral, disgruntled at having to copy a text in which Augustine was quoted incorrectly, drew a depiction of the saint pointing a spear at the offending passage while holding a scroll that reads “non ego” (literally “not me”, i.e. “I didn’t say that”).

Augustine recants his previous statement about wives and commits himself to a life of celebacy.

By the time the Rutland Psalter was created, around a century later, this culture of spontaneous margin illustration had grown in popularity and taken on a life of its own. The margin increasingly became a space for planned decoration, too, as artists experimented with illuminated initials. Large and complex letters inhabited by plants, beasts, and people had always been present in medieval manuscripts as a form of embellishment and a means of delimiting sections. As their contents often related to the adjacent text, initials were also a means of emphasising or commenting on its themes. But over the 13th and 14th centuries, these letters and their inhabitants began to spill into the margins and across the pages of books into self-contained scenes and borders independent of the letterform.

At the same time, demand for books, particularly illustrated books, grew among the upper class who prized them as a symbol of wealth. To cope with this new market, manuscript production gradually became the domain of secular scribes and artists who worked in teams to produce highly decorated prayer books for wealthy patrons. As the industry became separate from the church, motifs from folklore, popular culture, and everyday life joined the inhabitants of margins.

By the 15th century the opulence would peak, with full-colour lifelike illustrations filling every inch of available space in the most expensive books. The decorated initial was not altogether abandoned, but became less important as artists gradually assumed the freedom to illustrate beyond its confines.

Pages from the Prayer Book of Charles the Bold, Flanders, ca. 1470-80

While the pages above represent a culmination of manuscript grandeur, the Rutland Psalter, 200 years its senior, could be considered a first foray into this new generation of manuscript art. Created at a turning point from sacred to secular, functional to decorative, the Rutland Psalter displays qualities of both its forebears and descendants, the product of an artistic tradition still finding its feet.

In fact, it is the first known example of an English manuscript to display those highly decorated margins that would become so ubiquitous. Though it was likely not made by or for members of the Church, its artists were no doubt heavily influenced by the tendency among medieval religious scribes to use art as commentary. At the same time, they seem to have enjoyed the freedom to explore new styles and subjects in their work.

I can’t recommend enough that you look through the Rutland Psalter yourself: there’s brilliant artwork on practically every page. And luckily for you, the whole thing is digitised here!

A quick note from me!

Hi, it’s Olivia, aka weird medieval guys :) If you’ve made this this far, thank you! I appreciate every single person who clicks on my page. I love writing these articles and want them to be interesting and high-quality: often I spend a full day or more writing each one!

I apologise for not being more active in the past month on here. I’ve been working like heck since last autumn trying to balance a full time job, WMG, and some other very exciting things which will be announced later this summer. It’s honestly been a blast and I don’t regret any of it!

However, the degree of plate-juggling has gradually become difficult for my brain and body to maintain :( Thus, I’ve decided to leave my job so I can focus on my personal health and medieval guys for a few months. One of my main goals is to be more active on Substack during that time and put out more articles for you guys, especially my recently-neglected paying subscribers! To that end, I just wanted to remind you guys that you can become a paid subscriber to this newsletter for $10 a month (or less if you pay annually!) and that now more than ever I am so so so grateful for every one of you who has chosen to do so!

I will be adding more exclusive content this month for you guys and just want to give you (and my wonderful free subscribers) a huge thank you for giving me the support and love that a young frog like myself needs to keep WMG going!

This is so brilliant, Olivia. Such a great read, a treasure-filled joy. Delighted to hear more is on the way...

This is brilliant!