The use of the word clue in the sense of “a hint or helpful piece of guiding information” is a more recent one. Previously, clue, often spelt clew, meant a ball or other round mass of material, in particular a ball of thread.

Though somewhat archaic now, clew was used in its original sense well into the modern English period, including by Shakespeare. In All’s Well That Ends Well, our heroine Helen is spurned by her two-timing rapscallion love interest Bertram who abandons her right after their wedding. When Bertram’s mother, the Countess of Roussillon, hears the story from Helen, she is aghast. Though Helen is ashamed to confess Bertram’s behaviour, the Countess implores her to speak the truth:

You love my son. Invention is ashamed

Against the proclamation of thy passion

To say thou dost not. Therefore tell me true,

But tell me then ’tis so, for, look, thy cheeks

Confess it th’ one to th’ other, and thine eyes

See it so grossly shown in thy behaviors

That in their kind they speak it. Only sin

And hellish obstinacy tie thy tongue

That truth should be suspected. Speak. Is ’t so?

If it be so, you have wound a goodly clew;

If it be not, forswear ’t; howe’er, I charge thee,

As heaven shall work in me for thine avail,

To tell me truly.—As You Like It, Act 1, Scene iii

Or, in simpler terms: if you’re telling me what I think you’re telling me, and I think you are, then dear lord, what a tangle you’ve found yourself in!

Clew carried an implication of things congealed or knotted together. A ball of thread was perhaps the most common usage, but a knot of people—or in Helen’s case, problems—could be a clew as well. One of the few ways in which the term’s original meaning has survived into the modern day is apparently as the proper way to refer to a ball of worms. I don’t spend enough time amidst large quantities of worms to have first hand experience, but I am told that their clumping together into a slimy mass is a phenomenon common enough to necessitate its own name.

This sense of “something which has been balled or congealed together” preserves the original root of the word, which had very much the same meaning. It’s a connotation that is shared by many other words with the same root, including cluster, congeal, and, charmingly, jelly, gelatin, and gelato, which evolved via the Latin term for freezing or frost. Ice, jelly, a ball of thread—these things are all the product of some creative act or force. It has even been suggested that the word child descends from the same Proto-Indo-European root, the implication being that a child is something balled up or amassed in the womb in the ultimate act of creation.

The creation of thread and fabric is a common motif in folklore around the world, especially as a representation of the giving of life. Because both childbearing and the making of cloth were historically associated with women, it is no surprise that most of our mythical spinners and weavers are female, nor that their craft often signifies extraordinary power. If women can work the magic of creating new human life, might their other acts of creation be miraculous, too?

There are many cultures in which a fertility goddess is also closely associated with spinning and weaving, such as the Norse Frigg and the Maya Chac Chel. Of course, a classic example of this phenomenon is the Ancient Greek Fates or Morai, three women who quite literally spin, measure out, and cut the threads of human life.

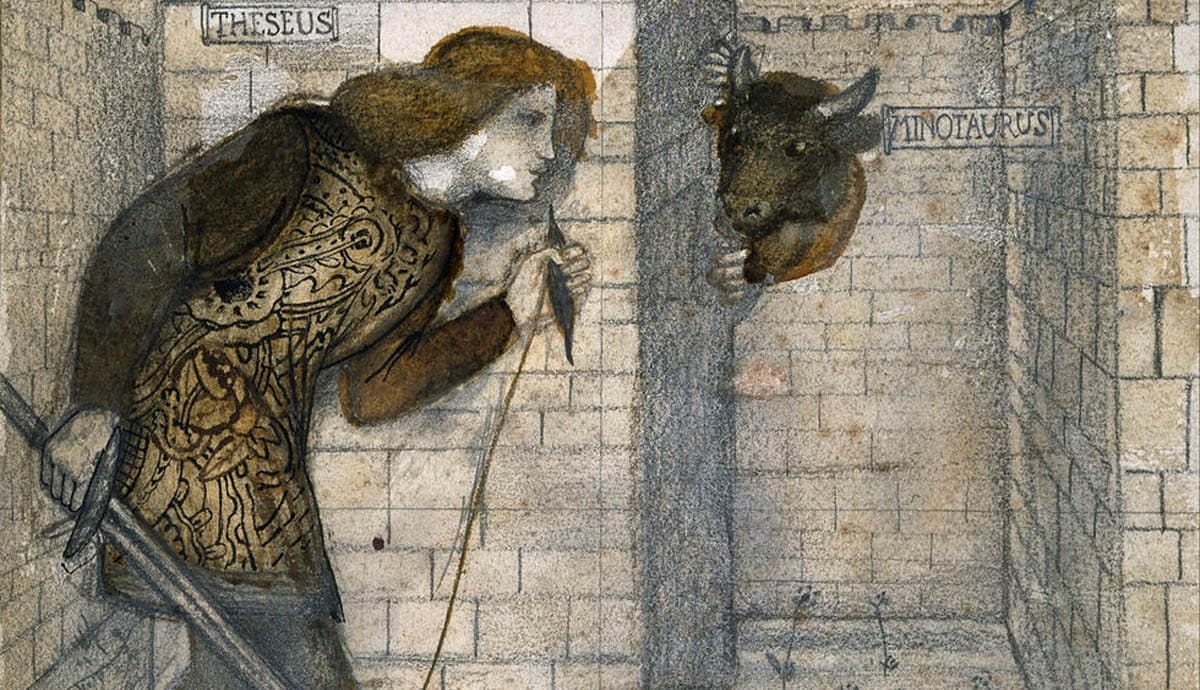

Similar themes appear in the myth of Theseus, the legendary Greek hero who ventured to Crete in the hopes of slaying the monstrous man-bull known as the Minotaur. Countless Greeks had already perished in the labyrinth where the Minotaur dwelled and the same fate may well have befallen Theseus had he not caught the eye of a Cretan princess named Ariadne. Smitten with the young hero, she gave him a clew of thread: a literal lifeline which he fastened at the entrance of the maze so he could retrace his steps back to safety once he had slain the beast.

Theseus’ trip back to Greece wasn’t quite as glorious as his exploits in Crete. According to most versions of the myth, he sailed off with Ariadne in tow only to abandon her before reaching home, sneaking off when she fell asleep on the beaches of Naxos1. Worse still, Theseus had promised his father King Aegeus that if he was successful in his mission, his ship would return to Athens with white sails instead of the black ones with which they had departed. If Aegeus saw a black-sailed ship approach the Athenian harbour, it would mean that his son had died. However, Theseus forgot to make the swap. When Aegeus spotted black sails on the horizon, he was so stricken with grief that he threw himself off the Athenian cliffs and into the sea, just a few minutes before his son arrived home safe and well.

Luckily for Theseus, it is not these little lapses in judgement for which he is best remembered. No, our picture of him is that of the intrepid young hero walking into the abyss with nothing but his sword and a ball of thread—his clew. So great is the power of that image that the word clew took on an additional meaning in English: not a tangle or snarl but the thing that leads us out from the tangle. The spelling was sometimes still clew rather than clue before the latter became standard, but the word was the same in either case.

When I read the book, the biography famous,

And is this then (said I) what the author calls a man's life?

And so will some one when I am dead and gone write my life?

(As if any man really knew aught of my life,

Why even I myself I often think know little or nothing of my real life,

Only a few hints, a few diffused faint clews and indirections

I seek for my own use to trace out here.)—Walt Whitman, "When I Read the Book"

In most versions of the story, the abandoned Ariadne is then discovered by the god Dionysus, who marries her. Some sources say that Dionysus demanded Ariadne from Theseus, while others claim that she was already married to the god before she eloped with Theseus, and that Dionysus killed her on Naxos when he learned of the betrayal. Plutarch has a very charitable interpretation of the whole scenario: according to him, the two were separated accidentally while trying to land Theseus’ ship during a storm.

A clew is also part of a sail. It’s the attachment point at the bottom/ back of the sail. (The foot and the leach). Usually made of several layers of fabric, with a reinforcing ring secured by twine.

Totally Fascinating. In the 16th ‘word fight’ poem, The Flyting of Montgomery and Powart, the Scottish goddess of witchcraft, Nicnevin, ‘casts a clew’—a tangled mess, a thread of fate, or a way out—a path clearing spell. Thanks for posting about this.