My favourite etymologies: "to curry favour"

Or, the unfathomably dark depths of the equine soul

The first of my series on particular etymologies is the story behind the phrase to curry favour. Somewhat counterintuitively, it has nothing to do with the word favour, and a lot to do with…horses!

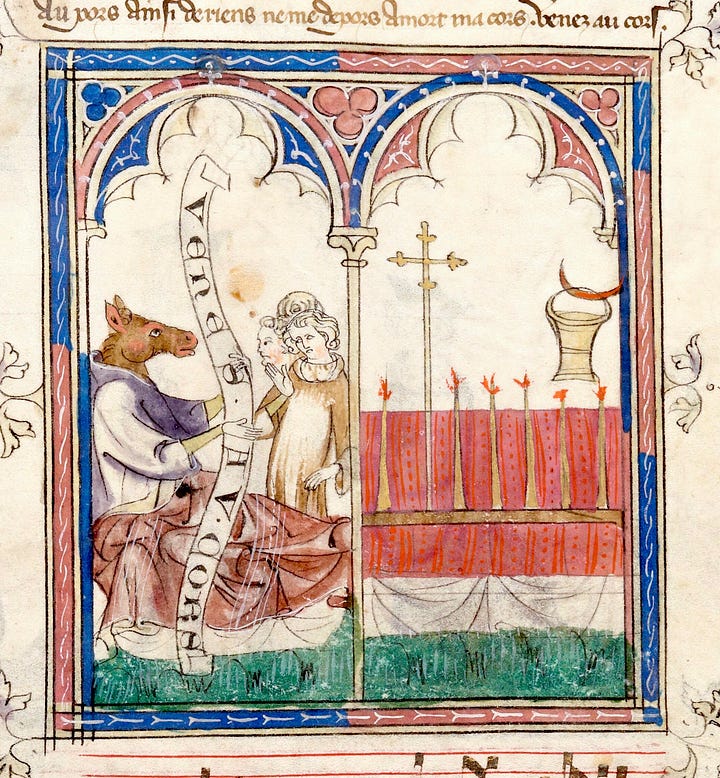

Our story begins in 14th century France with a poem. About a horse. This poem, the ultimate origin of currying favour, is called Le Roman de Fauvel, or “the Romance of Fauvel.” Romance being the original sense of the word—not a love story necessarily but a grand and fantastical tale—and Fauvel being the name of its main character, who is a horse. Fauvel isn’t just any old horse, though. He’s a naughty horse. Maybe the naughtiest horse there ever was1.

The 3,820 rhyming couplets that make up the poem are dedicated to informing the reader in great detail of Fauvel’s misdeeds and character deficiencies, which are many. For starters, his coat is fallow, the colour of mud, barren fields, and vanity. Our next clue to Fauvel’s unsavoury nature is his name. Spoken aloud, it sounds like faux veil, or “veil of falsehood.” It’s also an acronym, wherein each letter stands for one of the vices that Fauvel embodies.

F: Flattery

A: Avarice

V: Villainy2

V: Variability

E: Envy

L: Laxity

That’s pretty damning stuff, especially for a horse. What could Fauvel have possibly done to make himself the object of such ire, you ask?

Once an unremarkable horse, Fauvel was raised from the ranks by Lady Fortune herself in a sneaky coup against Lady Reason. Fortune swaps out Fauvel’s stable for the royal palace and bestows immense power and privilege upon the wretched steed so that he may reign over the world of men. Fauvel deposes the old nobility and installs his own court populated by anthropomorphised vices such as Gluttony, Lechery, and Drunkenness3. Not only is Fauvel blessed with immense material wealth but also with the adoration of his greedy, self-serving human subjects who have embraced his sinful ways.

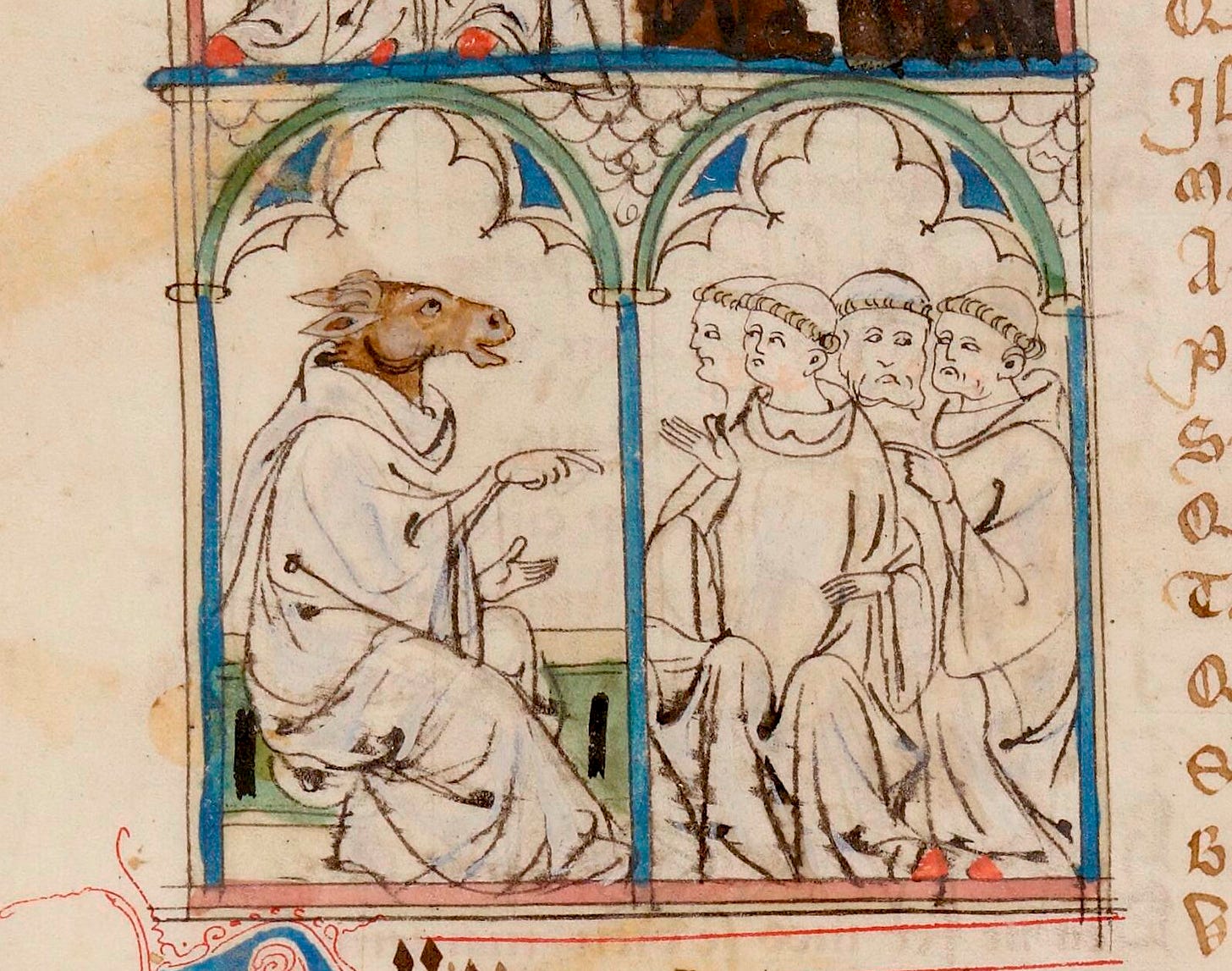

The natural order of all things is reversed. As the fallow beast beast becomes ever more human in his manners and lifestyle, we are told that men of the world have become more and more like ignoble beasts who fix their gazes not on the heavens but on the dirt beneath their feet. Humans of all walks of life, from humble peasants to the King himself, travel from across the land to prostrate themselves before Fauvel and groom his tawny coat in the hopes of gaining his favour. Even the Church has given in to Fauvel: the Pope has lost all power and the clergy answer to their new equine leader.

This invective against Fauvel continues for some time (1,300 verses, more or less), but the upshot throughout is essentially the same: Fauvel is corrupt, godless, sexually immoral, and evil, and has induced these qualities in all of society. The author laments that his land has fallen into the throes of horse-induced degeneracy and begs the reader to keep an eye out for Fauvel so they don’t fall victim to his tricks.

After this, though, the narrative really starts to kick off. The rest of the story concerns itself with Fauvel’s efforts to secure a wife. His first prospect is Lady Fortune herself. Though Fortune has been kind to Fauvel, he fears that the notoriously fickle dame could just as quickly turn against him. Matrimony, he hopes, might keep her on his side. Alas, Fortune sneers at the prospect, rebuffing his persistent advances with critiques of his foolish and greedy ways as well as discourses on the nature of fate, God, and humanity until the sorry horse is left heartbroken and declares himself ready to die. Taking pity, Fortune offers Fauvel one of her handmaidens, Lady Vainglory, as an ersatz bride.

Fauvel, all too happy to accept, trots off home with his betrothed to prepare for a wedding celebration befitting a horse of his status. Lured by the prospect of food, drink, and debauchery, vices flock to Fauvel’s palace en mass and the party commences. A great tournament is planned as the wedding’s centrepiece, but as contestants prepare, the second group gatecrashes the feast: the kingdom’s long-lost virtues, come to take up their lances and meet the vices on the jousting field. One by one, the vices are unhorsed by their betters. Carnality falls to Virginity, Pride to Patience, Fornication to Chastity, and so on, until all of the vices have been defeated.

However, we learn that Fauvel’s reign is far from over as Lady Fortune appears on the scene to deliver a final message. She tells Fauvel that though he will one day fall, he will cause much more damage to the world before that time comes. At this, she departs and so does Fauvel, who returns home with Lady Vainglory and sires many unholy offspring, all of whom inherit their father’s corrupt nature. The virtues are forced to retreat once more into the homes of the faithful few who have continued to harbour them in secrecy until all that is good can safely reemerge from the shadows.

The Roman de Fauvel seems to have enjoyed a warm reception in its day. More than a dozen surviving manuscripts show that the text was popular well into the fifteenth century. One version, which interpolates 169 pieces of choral music of various genres into the story, has led to speculation that Fauvel may have been staged as a play or sort of proto-musical, though it’s hard to imagine audiences sitting through what would have been hours of dithering love songs delivered by a sinful horse.

Fauvel pops his horsey head up in a few other works of the following decades. One, the Roman de Fauvain, features a purported relative of Fauvel and his equally devious deeds. Fauvain’s story, however, reaches a perhaps more satisfying conclusion when he dies and goes to hell. A manuscript illumination depicting Fauvain’s end shows his little equine soul departing his body to be received into the open arms of a demon.

However, the Roman de Fauvel and its antihero seem eventually to have faded from European cultural memory—perhaps unsurprisingly so. Though the Roman de Fauvel bears similarities to more enduring romances of the day such as the Roman de la Rose, its constant moralising and lack of any positive figures or themes make it feel rather dour in comparison. Perhaps a better comparison to Fauvel would be the fables of Reynard the Fox, another devious animal of medieval folklore. But Reynard is a more archetypal trickster, like Tom Sawyer or Bart Simpson—an endearing social outcast who’s always one step ahead of his rivals. Naughty but clever, he uses wit to exploit the witless and corrupt. You can’t help but root for the trickster even when you know they’re morally wrong because the trickster is relatable or even aspirational; someone crafty enough to cut corners and live by their own rules.

Crucially, the trickster uses their wit to expose shortcomings in society. Fauvel, conversely, embodies and even induces these same shortcomings. Superficially, he is a horse, but he is a horse composed of pure evil; he is set up by his author not so much as an example of vice but as an essential form of it, unabashed wickedness wearing the skin of a barnyard creature, a being whose depravity is so virulent it has infected the entire world.

Of course, there is an allegorical layer to the text. This article has gone on long enough, so I won’t get fully into the background behind who wrote the Roman de Fauvel and why, but it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise to hear that Fauvel is a stand-in for the king of France who reigned during the author’s life and that the author wasn’t too happy with the nobility or the church at the time, either. In that context, Fauvel-as-allegory holds a bit of water, but only a bit. If you’re going to write a story whose message effectively amounts to “everything was fine until this evil horse showed up and made everything bad,” that’s a message that really only works in the context of the horse being a metaphor for one specific guy that you really hate.

Most fables about animals seem to use them as a way of simplifying moral messages—be like the persistent tortoise, not the arrogant hare! Even people who are quintessentially ugly like frogs can still be nice! The animal embodies one aspect of human behaviour, either good or bad, and experiences the consequences thereof. The message is that you should learn from it, because while the animal cannot control its own behaviour, you can. Fauvel, on the other hand, tells us that true evil walks among us in the form of a wicked beast, and if we do not remain on constant guard, we too will become corrupt and satanic and beastlike. In this regard, his closest literary parallel is more likely to be the Beast of the Apocalypse, or perhaps the pale horse ridden by Death, which was after all sometimes depicted in medieval manuscripts with a tawny or mud-brown coat.

That’s not to be too down on Fauvel. After all, he was very popular in his day. I’m sure the gravity of his Roman’s themes juxtaposed with its satirical style—which parodied conventional love stories of the day—made for some very entertaining reading amongst the late medieval francophone literati. And horses possess a certain innately puckish quality that is captured beautifully in illuminated editions of the Roman de Fauvel. But although Fauvel clearly spoke to some sort of fourteenth-to-fifteenth century zeitgeist, he seems to have been largely irrelevant by the sixteenth century. Europe’s first printing presses churned out copies of Robin Hood, The Canterbury Tales, Le Mort D’Arthur, The Divine Comedy, The Romance of the Rose, The Travels of Marco Polo, and other familiar medieval tales, but nobody printed Fauvel. The modern world didn’t want him. I suppose that, like a silent film starlet whose career was ended by the talkies, he just didn’t have the range.

Perhaps the most enduring impact that Fauvel had on popular culture was in the form of his name, which he lent to a common turn of phrase: to curry4 Fauvel, meaning to flatter or praise with the intention of gaining favour. Currying here means a type of grooming with a brush made to clean and smooth a horse’s coat, just as Fauvel’s sycophants would groom his coat in the hopes of winning his approval. The phrase seems to have remained well-known in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries even as Fauvel and his tale did not5. As is often the case in early modern English, spellings vary wildly: by 1475, versions such as correy famelle, conraye fawenelle, and cory favyl appear.

By the mid-sixteenth century, some writers seem to have a poor grasp on the term’s original sense. English printer John Awdeley published a short pamphlet in the early 1560s titled The Fraternitye of Vacabondes in which he catalogues the different types of beggars, street swindlers, and ne’er-do-wells of his day and their tricks. Awdeley warns against such characters as the Ruffeler, Whipjack, Irish toil, Choplogyke, Simon-soon-a-gone, Palliard, Munch-present, and of course the notorious “Cory fauell [sic].” Awdeley describes the Cory fauell thus:

Cory fauell is he, that wyl lye in his bed, and cory the bed bordes in which hee lyeth in steede of his horse. This slouthfull knaue wyll buskill and scratch when he is called in the morning, for any hast.

So, to Awdeley, a curry-favour was some sort of layabout who spent all morning fiddling with his bedsheets (or something along those lines) rather than keeping his horse in good nick. How foolish.

And then, in 1580, we finally see it, in the first edition of John Lyly’s Euphues and his England. The phrase “to curry favour6.” Well, technically “to currey fauour.” But the change has been made! Good-bye, Fauvel! Clearly, his name has become so obscure to the average English speaker as to be nonsensical. The human brain, doing what it does best, has filled in the gaps with something more recognisable. Favour. Thenceforth, to curry favour seems to have gradually become the dominant form, as it remains today.

N.B. Unless otherwise mentioned, all images of Fauvel are from Bnf, Français 146

EDITED 08/03/2025: Thank you to

for alerting me to the fact that there is indeed an English translation of the first book of the Roman de Fauvel and it is available for free online download! Sadly, there is as far as I can tell still no English translation of book II, which contains Fauvel’s courtship of Lady Fortune and marriage to Lady Vainglory.N.B. To the best of my knowledge, a full English translation of the text has not been published. The information in this article is drawn mostly from English-language secondary literature with the occasional supplement from a public domain French critical edition. EDITED 08/03/2025: Thank you to

Although the consonant sound V and the vowel sound U were distinct in medieval French and English, the two letters were considered to be variations of the same letter and were used interchangeably until the 16th century. So, the acronym sort of works better if you imagine you’re a 14th century French speaker.

Actually, I went through the French text and translated as many as I could find, so if you’re curious, here’s a more complete list of Fauvel’s court of vices: Sadness, Ire, Grudgery, Hatred, Trickery, Falsehood, Guile, Pride, Counterfeit, Carnality, Lust, Avarice, Idolatry, Envy, Denigration, Gluttony, Drunkenness, Lechery, Presumption, Despair, Indignation, Vanity, Covetousness, Boastfulness, Presumptuousness, Inconstancy, Cowardice, Doubleness, Ingratitude, Villainy, Anguish, Murder, Treason, Robbery, Gambling, Trickery, Debauchery.

Etymologically unrelated to the family of sauce-based dishes of the same name.

This is probably due in part to the fact that before the Roman de Fauvel was written, Fauvel already existed as a generic name for a fallow-coated horse, being derived from the French fauve, meaning fawn-coloured. A bit like naming an orange cat “Ginger” or a spotted dog “Spot.” As far as I’m aware, though, neither the name nor the coat colour had any negative associations attached to them before the publication of the Roman. Richard the Lionheart apparently had a horse named Fauvel and I don’t think Richard had any bother with him.

There may well be an earlier usage, but this was what a good hour or so on Google and Internet Archive turned up. I did find an example in a 19th century reprint of a 1577 text called Fiue Hundred Pointes of Good Husbandrie, but with no way to be sure that this was the spelling used in the original, I have opted to name John Lyly’s text as my earliest example.

'Currying being a type of grooming that uses a brush made to clean and smooth a horse’s coat, etymologically unrelated to the family of sauce-based dishes of the same name.'

See, this is when footnotes come into their own. I've never been unduly concerned about the favour, it was the currying that gave me pause

That is amazing! You are the Hercule Poirot of investigating language origins! Thank you for a great read!